The Islamic Religion is Often Mixed With Cultural Practices

http://www.vexen.co.uk/religion/islam_religion_and_culture.html

By Vexen Crabtree 2011

#atheism #christianity #islam #judaism #religion #statistics #UK

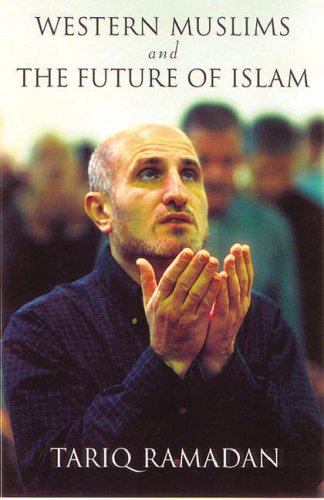

“Islam is not a culture. Whether we like it or not, the essence of Islam is religious.”

“Islam is not a culture. Whether we like it or not, the essence of Islam is religious.”

"Western Muslims and the Future of Islam" by Tariq Ramadan (2004)1

Ramadan argues that Western Muslims need to learn to observe Islam without letting local cultural practices interfere.

Islamic practice is often a mixture of cultural norms mixed with formal Islamic law, resulting in a "curious mixture of unity and diversity"2 that varies quite a lot from country to country (all religions have such a spread). It is often difficult to see which is which and without an understanding of what is meant by "Islam", and in the face of such cultural pluralism, some scholars refer to "Islams", which Ramadan criticizes as being sourced in the confusion between culture and Islam. Muslims themselves conflate the two things, especially if adherents in a country cannot speak the language that the original scriptures are written: Western Muslims do not generally speak Qu'ranic Arabic. This is made worse if, as is the case in much of the West, there are no local and authoritative Islamic institutions that are unconnected to national churches from Eastern Islamic countries.

“

Organized religion is normally represented by an established body of professionals partially because these people very often have the greatest access to the mass media. But in an era now defined by globalisation, free expression and by access to the Internet, we know that almost every group of believers is more diverse than it appears from the outside. "Wherever we go, we will find that religious concepts are much more numerous and diverse than 'official' religion would admit" writes the sociologist of religion Pascal Boyer (2001)3. Another academic says "religion may be studied by referring to its established, official mode; it may be studied in its manifold popular varieties"4. The grassroots religion is frequently a mixture between common culture and a set of practices which have been called a 'religion' by others. Villages and counties can sometimes adopt a new religion and the only outward signs are that the shrines in the local places of worship get new figurines, or, the gods and spirits get new names and updated stories. The practices themselves are sometimes what the religion is, no matter the named theology that is placed on top of them to explain them. A top-down change will often fail to change the practices on the ground. Grassroots changes are hard to predict or control. Take Hinduism... the religion itself is a collection of folk practices, sayings, stories, traditions that we Westerners took to categorize under a single name5. Hinduism is a grassroots religion. Also take as an example the Reformation and other top-down attempts at changing the religious landscape in the UK; they nearly all failed, resulting merely in name-changes. Westerners (and Muslims themselves) often cannot tell the difference between cultural practices of the countries of origin, and the practices grounded in Islamic law. Without study, culture and religion are often confused even in Abrahamic religions that you might expect to be purely scripturally-driven.”

Anti-Islamic discourse will often have as its motivator a great distaste for many practices apparently connected directly with Islam, such as female genital mutilation and a heavy oppression of women. Yet often, the practices in question are actually cultural, tied in with the common culture of home countries. These practices could mostly or largely be dropped without breaking Islamic law. In reality, though, Islam itself does set the ground, the theological background, which allows such practices to be followed. If Islam itself was kinder towards women, for example, many of the cultural practices that go against international human rights could be curbed much easier in Islamic communities. The Muslim scholar Ramadan devotes a chapter of his "Western Muslims and the Future of Islam6" to the confusion between culture and religion amongst Western Muslims and argues that the cultural side of things is often the biggest problem.

“The Muslim women and men who emigrated from, for example, Pakistan, Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, or Guyana brought with them not only the memory of the universal principles of Islam but also, quite naturally, the way of life they followed in those countries. Moreover, to remain faithful to Islam meant, in the minds of first-generation immigrants, to perpetuate the customs of their countries of origin.”

"Western Muslims and the Future of Islam" by Tariq Ramadan (2004)1

Hopefully, keeping in mind the distinction between culture and religion will hope shed light on some Islamic apologists who say that certain things "are not part of Islam" even when it appears to observers that they are clearly associated - this is the result of Arabic cultures happening to be the place where Islam arose, and Islamic practice is still a mixture of those cultures plus formal Islamic law.

All this has an impact on sociological surveys and the resultant national statistics of belief:

“Once a religion has become institutionalized or popular, some trends appear that serve to exaggerate statistical measurements of the numbers of adherents (followers) it has. Firstly, people start telling officials that they 'are' a religion for traditional reasons to do with family rather than because it is what they truly believe. Secondly, people start exaggerating how much they are engaged with the religion, i.e. how often they attend religious events such as going to Church on Sunday. Thirdly, the religion itself becomes more diverse and so encompasses a greater number of believers in various things. Fourthly, cultural norms merge with religious norms to produce distinctive practices that are hard to separate into pure categories of religion or culture, meaning that some religionists follow cultural norms without actually believing in the religious side (hence the appearance of atheist Jews, etc). Fifthly and finally, a large number of theologically-illiterate laypeople will confuse any generally religious beliefs with whatever the dominant religion is in their community. So, in Christian countries those who merely believe in God are called Christian whether or not they believe in the complications of Christian theology, but in Muslim countries those same people would call themselves Muslim because they believe in God, whether or not they believe in Islam. Established and traditional religions are over-represented in polls.”

"Institutionalized Religions Have Their Numbers Inflated by National Polls" by Vexen Crabtree (2009)