Do We Need Religion to Have Good Morals?

https://www.vexen.co.uk/religion/ethics.html

By Vexen Crabtree 2014

#atheism #ethics #human_development #morals #religion #religious_morals #secular_morals #theism #UK

Many theists have argued that "without God there can be no ultimate right and wrong"1,2,3 and that society cannot manage without religion4,5. In 2017 Dec, Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, argued in an ignorant outburst that inclusive and non-religious schools (and parents) lack values6. The French President, Nicolas Sarkozy, supported the idea that you can't have good morals without religion7. Karen Armstrong, who is often criticized for romanticising religion, says that "we need myths that will help us to identify with all our fellow-beings [and] that help us to realise the importance of compassion, which is not always regarded [sufficiently ...] in our pragmatic, rational world"8.

On the other hand, since The Enlightenment the Western world (finally) came to widespread acceptance of the idea that people can think for themselves outside of enforced ethical frameworks9. In non-religious countries such as the UK, most people state that morality doesn't require religion and that the latter causes more harm than good10. What does the evidence say? Unfortunately the statistics are not in favour of the proponents of the moral worth of religion. The most unstable, violent, intolerant countries with the worst human rights records, are all highly religious, and, the least-religious countries are also those that are performing best in terms of social and moral development.

- Evidence That We Do Not Need Religion For Social Morals

- Religious Belief Systems and Morals

- Deriving (Absolute) Morals from Religious Texts

- Human Rights and Secular Morals: Ethics Without Religion or Faith

- Links

1. Evidence That We Do Not Need Religion For Social Morals11

1.1. The Social and Moral Index

#atheism #ethics #morals #religion #religious_morals #secular_morals #theism

Source:12

The Social and Moral Development Index concentrates on moral issues and human rights, violence, public health, equality, tolerance, freedom and effectiveness in climate change mitigation and environmentalism, and on some technological issues. A country scores higher for achieving well in those areas, and for sustaining that achievement in the long term. Those countries towards the top of this index can truly said to be setting good examples and leading humankind onwards into a bright, humane, and free future. See: Which are the Best Countries in the World? The Social and Moral Development Index. The graph here shows clearly that social and moral development is at its highest in countries that are the least religious. As religiosity increases, each country suffers from more and more conflicts with human rights, more problems with tolerance of minorities and religious freedom, and problems with gender equality. Although it could be argued that the correlation is only coincidental, this at least is powerful evidence against the idea that religion is required for societal moral health.

There is one interesting pulldown in the curve along the horizontal positions inbetween the 55% and 25% rate of religiosity. This is caused by a clutch of countries that have both medium levels of social and moral development, yet are also not particularly religious. They are all ex-communist nations, where religion was supressed.

“The empirical evidence does not support the widespread assertion that religion is especially beneficial to society as a whole. [...] It is not clear how society is any better off than it would have been had the idea of gods and spirits never evolved.”

"God, the Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist"

Prof. Victor J. Stenger (2007)13

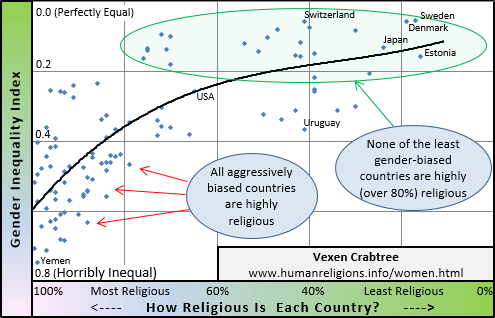

1.2. Gender Equality

#gender #gender_bias #gender_inequality #religion #women

Source:14

The graph (right) clearly shows the negative association between religion and gender bias. None of the most equal countries are highly religious, and, all of the horribly inequal countries (scoring worse than 0.4 on the index) are highly religious.

For more, see:

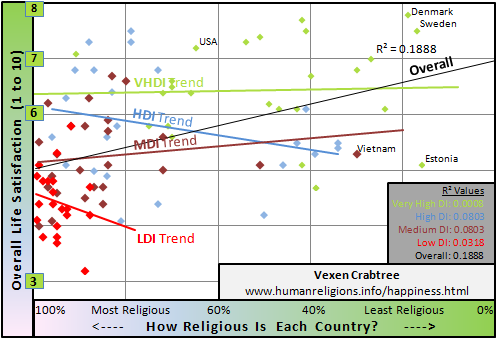

1.3. Happiness

#happiness #human_development #religion #religions #secularisation

Aside from measurable issues of morality and tolerance, violence and crime, there are other less haughty human factors which sociologists have measured.

Religious believers often say that their religion makes them happy and that this is one of the reasons for them remaining loyal to their religion17,18. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was distraught by this, blurting out that no-one should "regard a doctrine as true merely because it makes people happy... happiness and virtue are no arguments"19. But even more unfortunately, it happens that across the world, religious countries are unhappier than non-religious ones20.

“Adrian White, a University of Leicester psychologist [analyzed] more than a hundred studies that questioned eighty thousand people worldwide. [...] White's work clearly shows that high levels of belief do not guarantee high levels of happiness for societies. Based on the data, high levels of nonbelief seem more conducive to a society's overall happiness than belief.”

Adrian White

Science Daily (2006)21

For more, see:

2. Religious Belief Systems and Morals

2.1. Dogmatism and Legalism

Doctrine has often been specifically formulated with behaviour-control in mind. Origen, one of the founding (Christian) Church Fathers, argued that while the actual terrors of hell were false, they were useful for scaring simpler believers. Plutarch calls hell an "improving myth"22. But dogmatic and legalistic behaviour is not 'moral' behaviour. Simply obeying rules, tradition and dogmatic answers to moral questions does not make a person moral. Morality requires choices, and the more that a person relies on a "text book of morality" or pre-defined rules, the less they are acting as a moral person. Obeying rules because you think you should is not the same as making moral choices; therefore at best such people are morally neutral, amoral. It seems that as far as morality is complicated as soon as real-life situations are encountered, those best at it will be those who have long exercised their conscience while being free of enforced dogmas.

We have already seen Talcott Parsons worry that secularisation undermines the legitimisation of moral rules but he also describes the way in which societies become "adaptively upgraded" by loosening their embrace on dogma and religious authority: they become "more capable of responding flexibly and appropriately to a wide range of dangers and opportunities".

“Beliefs may become so general that they lack any specific or necessary relation to particular values, and the values themselves can no longer provide a firm grounding for the society's basic rules. People follow the rules, regardless of their values, and they hold their values, regardless of their beliefs. What Parsons calls the cultural system therefore loses its grip on the social order. Beliefs and values, rules and regulations float more or less independently in a sea of cultural options that lack any logical or necessary relationship to each other. One can follow the rules because to do so is expedient rather than right. One can do the right thing because it is one way to avoid conflict or surveillance, regardless of whether one considers the right thing to be good. Furthermore, one can do what is good regardless of whether one thinks it is true or has any lasting value that transcends self. One's choices and ethics may be expedient or situational, and one's values can be utilitarian or relative to the society one belongs to, and one's beliefs may support one's values but lack and transcendent authority.”

"Key Thinkers in the Sociology of Religion"

Richard K. Fenn (2009) [Book Review]23,24

In "Utilitarianism" by John Stuart Mill (1879)25 the author notes that some religions in history, in particular Judaism, used to work on the principal that all laws ought to be derived from divinity, often, through divine texts and exegesis (which means the interpreting of holy texts), but adds a rather sensible refrain: "But other nations, and in particular the Greeks and Romans, who knew that their laws had been made originally, and still continued to be made, by men, were not afraid to admit that those men might make bad laws"26. This is great thinking: by allowing our laws to be gradually improved, we can edge forward morally decade by decade, working out what is workable and what isn't.

The evidence points very much to the fact that it is not a bad thing if the beliefs that underlay moral actions lack transcendental authority. It seems to be turning out in the long run that this is a good thing. The embrace of human rights, the greatest preventer of national and cultural abuse of minorities, for example, is promoted by secular organisations (the United Nations being the biggest of them), and, opposed strongly by religious organisations in every country.

2.2. Rewards and Punishment

“If people are good only because they fear punishment, and hope for reward, then we are a sorry lot indeed.”

Albert Einstein27

Theists have a two-pronged pair of incentives that serve to lessen the worth of any apparent moral act on their behalf. If I am threatened into behaving in a good manner then I am at best amoral, because I am not acting with free will. If you believe that a supreme god is going to punish you (in hell) or deny you life (annihilation) if you misbehave, it is like being permanently threatened into behaving well. In addition, if you believe there is some great reward for behaving well, then your motives for good behavior are more selfish. An atheist who does not believe in heaven and hell is potentially more moral, for (s)he acts without these added factors. Most atheists who do not believe in divine judgement, and most theists who do, both act morally. Some of both groups act consistently immorally. The claim that belief in God is essential or aids moral behavior is wrong, and any amusing theistic claim that they have "better" morals, despite acting under a reward and punishment system, is deeply questionable. Who is more moral? Those who act for the sake of goodness itself, or those who do good acts under the belief that failure to do so results in hell?

Consider the fates of these three people:

Out of all the religions, this person picks the one that sounds like it will give the best rewards after death.

This person simply accepts whatever religion he was born with, and tries to live his life as best he can.

Out of all the religions, this person doesn't know which to pick even though he studies them, so he tries to simply live his life as best he can, deliberating carefully over the moral stances that he takes.

Imagining for the moment that god is benevolent (good) and judges us, then, it is surely the third person who deserves most merit. The first person, who follows Pascal's Wager, is openly self-centered. Given that many religions proscribe punishments for those that worship the wrong god, the third position (pick no religion) is the safest of all three options.

Take as an example the lesson being taught in Proverbs 6:20-35 (See: Proverbs Chapter 6). It is about the reason for not committing adultery but it does not mention the suffering caused to other people's married lives, nor the immorality of the act: It solely talks about the seriousness of revenge that the husband might exact, and, about the importance of looking after your own skin. Even when giving good advice, it seems the Bible manages to miss the point of moral thought!

A good test of whether or not a person truly believes that God is necessary for morality is to ask them what immoral behaviour they would suddenly engage in if they ceased believing.

“If you agree that, in the absence of God, you would 'commit robbery, rape, and murder', you reveal yourself as an immoral person [...]. If, on the other hand, you admit that you would continue to be a good person even when not under divine surveillance, you have fatally undermined your claim that God is necessary for us to be good.”

"The God Delusion" by Prof. Richard Dawkins (2006)28

If a person is only behaving well because they are threatened by hell and want the reward of heaven, then, then this test reveals the underlying truth that good people are good no matter if they believe in god or not, and, bad people are bad even if they're forced or coerced into doing good.

You can gradually change character by reflecting on the flaws of your own actions and by receiving advice and instruction from people in your community and from reading. But, there is no particular need for this input to be religious. Indeed, those who use a codified system are often less adaptable and find themselves desperately applying anachronistic moral ideas to a world where they no longer fit.

2.3. Is Religion Required to Be a Good Person?29

Religions almost universally emphasize the moral duty of the individual. "God knows all" as the Qur'an and Bible repeat: examples in the Christian Bible include Job 28:24, 37:16; 1 John 3:19-20; and very frequently in the Qur'an: the first chapter (after the introduction) iterates God's omniscience ten times, for example Sura 2:29,77,85,115,137. We all answer to God eventually. Buddhism and Hinduism likewise teach that we pay the consequences of this life throughout our next. So many people come to think of religions as being a bastion of moral thinking, because, religions tend to dramatize and exaggerate the rewards and punishments of good and bad behaviour. Don't forget that when Psalms 14:1 says "the fool saith in his heart that there is no God", the word it uses in Hebrew also means immoral people: immoral people say 'there is no god'. This emphasis is strong amongst laypeople: despite their record against human rights on an institutional and national level, locally popular religions are often seen as a force for good and there is a general belief that religion supports morality30. A 2002 poll in the USA, an unusually religious country for its state of development, found that on average 44.5% of the adults believed that "It is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values"31. This included both church-goers and laypeople. 65% of regular churchgoers believed it, thinking therefore that the vast majority of the members of "wrong" religions therefore could not be moral people. This ridiculous belief is still held by 25.7% of those who never attend church. Although it is hard to believe that this level of ignorance can exist in the rest of the world, the underlying belief was more popular in pre-modern times throughout the world. Academics have also toed this line; Talcott Parsons in 1966 said the same thing, merely using bigger words. After saying that what makes moral rules valid is a 'legitimation system', he adds that 'a legitimation system is always related to, and meaningfully dependent on, a grounding in ordered relations to ultimate reality. That is, its grounding is always in some sense religious. [...] The process of secularization, then, undermines the system of legitimation by which a society's rules seem to be grounded in ultimate reality.'24

Bryan Wilson is an insightful and respected sociologist of religion. Even he, in 1982, warned of mass breakdown in morality in the West if the religious underpinnings of moral propriety were forgotten.

“As Wilson (1982: 52) concludes, 'Unless the basic virtues are serviced, unless men are given a sense of psychic reassurance that transcends the confines of the social system, we may see a time when, for one reason or another, the system itself fails to work...' [...] Wilson (1982: 86) describes how secularization resulted in the breakdown of morality in Western societies: 'When in the West, religion waned, when the rationalistic forces inherent in Puritanism acquired autonomy of their religious origins, so the sense of moral propriety also waned - albeit somewhat later, as a cultural lag. Following the decline of religion [... and the resultant] process of moral breakdown [... we should have] genuine concern about the role of morality in contemporary culture' (Wilson 1982: 87)”

"Religion in Sociological Perspective" by Bryan Wilson (1982)32

Being discussed in "Key Thinkers in the Sociology of Religion"

Richard K. Fenn (2009) [Book Review]23

After Parsons in 1966 and Wilson in 1982, Karen Armstrong repeats the same story in "A Short History of Myth: Volume 1-4" (2005)33, arguing that myth is essential for good ethics and meaningful living. How do all of these thinkers rationalize the fact that many god-believers, myth-believers and suchlike, appear to commit the same atrocities and immoralities as unbelievers? From the Dark Ages presided over by Christianity, to the spectre of Islamist brutality against (for example) women and gays in Islamic countries, it seems that religious morals are hardly a panacea. Karen Armstrong dismisses these problems with the odd concept that they are caused by "failed myths"34. An element of double-think appears to be in place: if religious people do good, it is because they are religious, whereas if they do wrong, it is because they are fallible human beings. Such circular logic ought to be challenged wherever it is heard.

So there are numbers of people who, if they want to be good or, wants to be seen as good, will gravitate towards religion simply because they think it is what required. These people, who have come to actively choosing to be a better person, will find that their efforts are rewarded whether or not they choose to do it within a religious framework.

There is plenty of evidence that religion is not required. Parson in 1966 and Wilson in 1982 both warned of systematic collapse in morality if secularisation continued. It not only continued, but has accelerated. There has been no mass failure. Crime is down, wars are shorter, violence is down. It happens that people can also adopt non-religious and secular philosophies in order to promote good moralizing. Secular movements such as the British Humanist Association and IHEU (International Humanist and Ethical Union) are devoted to encouraging moral behavior, moral thinking, overall conscientiousness and rationality. The main difference between these and religious groups who do the same, is that the religious groups often teach that they are the only valid source of morals.

2.4. Society's Morals Change Over Time, and Religion's Follow35

It is very telling that while society's morals change over time, religion's acceptance of new ideas (from human rights and equality to animal and environmental care) often lags behind by several generations. This hasn't always been the case; once upon a time, in general, moral thinkers were religious reflectives. Bryan Wilson, the esteemed sociologist of religion, records that instead of shaping the morals of secular society, religion in the West now slowly follows36.

An effect of this lag is that religions and sects that are stricter and more resistant to change their moral stances, find themselves increasingly at odds with society at large. This is particularly true in the realm of human rights; most campaigners are engaged much of the time in struggles against religious groups, religious lobbies, and religious activists who are opposed to various aspects of human rights. Typical battles occur over gender equality, tolerance of sexuality and the immorality of prejudice, abortion rights and women's rights, animal welfare - not to mention other topics such as science education. Newer religions fare better as they are founded on more modern morals.

| Prohibition | 1951 | 1961-3 | 1982 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studying on Sunday | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| Playing pool | 26 | 4 | 0 |

| Playing cards | 77 | 33 | 0 |

| Social dancing (tango, waltz, etc.) | 91 | 61 | 0 |

| Folk dancing | 59 | 31 | 0 |

| Attending 'Hollywood-type' movies | 46 | 14 | 0 |

| Smoking cigarettes | 93 | 70 | 51 |

| Drinking alcohol | 98 | 78 | 17 |

| Smoking marijuana | 99 | ? | 70 |

| Casual petting | ? | 48 | 23 |

| Heavy petting | ? | 81 | 45 |

| Premarital sexual intercourse | ? | 94 | 89 |

| Extramarital sexual intercourse | ? | 98 | 97 |

Source: Bruce (1996)37 | |||

In case anyone doubts it, statistical surveys have found that religious morals change over time too. There are many things that were once completely taboo for many Christians, but which now would only attract incredulity if you were to tell them that their forebears once held these things in anathema. The chart on the left highlights some changes amongst evangelicals, who are as a group highly vocal about the necessity of sticking firmly to the eternal morality sanctioned by God. It is clear that such sanction is quite open to exegesis (which means the way you can get various meanings from the Bible).

Take dancing; in the 9th century Church leaders gathered and condemned dancing in (and singing) in churches, calling it pagan and hoary38. Similar pronouncements occurred during the dark ages and as late as 1684, Puritan ministers in New England said the same39. It is hard to imagine a single preacher saying it now about classical dancing anywhere, let alone during worship.

The Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance (OCRT) examined how it is that such a changing kaleidoscope of religious morals can be derived from static and unchanging source texts:

“Religious groups use various methods to change their beliefs. Sometimes, the texts which support the old beliefs:

”

Are simply ignored;

Are reinterpreted. Passages previously interpreted literally are now interpreted figuratively; Sometimes the reverse happens.

Are regarded as having been valid at the era and/or the society in which they were written, but are not meaningful for guidance for people today.

Are considered to be ambiguous in their original language and are retranslated into English with a different meaning.

Are unambiguous in their original language, but are intentionally mistranslated into English to give an ambiguous meaning. One example of this is to translate the Hebrew word for "slave" into the English word "servant" which can refer either to an employee or a slave.

OCRT (2013)40

2.5. Mistaken Focus of Religious Ethics on the Mystical Individual

Religious systems of morality have an odd emphasis on internal thoughts, and often regard many attributes as positive that actually do no good for the world at large, such as (1) withdrawing from the world and (2) not engaging others when they have clearly done wrong, For example, consider the Catholic Church, which did not oppose the fascist Nazis at all in Europe and who opened their genealogical records so the Nazis could hunt Jews, and who didn't excommunicate Hitler for his crimes. The Catholic Church only selectively engages in politics, because its morality is too concentrated on individual sins, such as adultery, and not political ones, such as genocide or human rights abuse.

“The natural impulse of the vigorous person of decent character is to attempt to do good, but if he is deprived of all political power and of all opportunity to influence events he will be deflected from his natural course and will decide that the important thing is to be good. This is what happened to the early Christians; it led to a conception of personal holiness as something quite independent of beneficent action, since holiness had to be something that could be achieved by people who were impotent in action. Social virtues came therefore to be excluded from Christian ethics. To this day conventional Christians think an adulterer more wicked than a politician who takes bribes, although the latter probably does a thousand times as much harm. The mediaeval conception of virtue, as one sees in their pictures, was of something wishy-washy, feeble, and sentimental. The most virtuous man was the man who retired from the world; the only men of action who were regarded as saints were those who wasted the lives and substance of their subjects in fighting the Turks, like St Louis. The Church would never regard a man as a saint because he reformed the finances or the criminal law, or the judiciary. Such mere contributions to human welfare would be regarded as of no importance. I do not believe there is a single saint in the whole calendar whose saintship is due to work of public utility. With this separation between the social and the moral person there went an increasing separation between soul and body, which has survived in Christian metaphysics and in the systems derived from Descartes.”

"Why I am not a Christian" by Bertrand Russell (1957)41

“Without doubt the greatest injury ... was done by basing morals on myth, for sooner or later myth is recognized for what it is, and disappears. Then morality loses the foundation on which it has been built.”

Viscount Samuel (1870-1963), British statesman and philosopher, high commissioner for Palestine (1920-5) and home secretary (1916, 1931). Wrote "Philosophy and the Ordinary Man" in 1932

Not only has the monotheistic system of ethics come to be based on non-Human and non-societal fantasy, but it is actively anti-Human and anti-societal. Theist morality is given justification on the basis of their beliefs. But reasonable thought, good intentions and good character all produce good morals in action, and produce them in a more fluid, sensible way. What we base on myth and religion and then write in stone, becomes stagnant, legalistic and cold: What we base on love and reason is a superior form of morality to what we derive from religion. As Viscount Samuel notes, if we base our morals on religion, sooner or later the foundation will be lost. In addition to that, it is misguided to base morals on religion in order to claim that they are unchanging as religious morality changes over time just as secular morality does, the only difference is that non-religious folk admit the change and short-sighted religious folk don't admit it. Secular morality is more honest.

3. Deriving (Absolute) Morals from Religious Texts

3.1. Subjectivism Prevents the Revealing of Absolute Morals

#biblical_inerrancy #christianity #epistemology #god_communication #islam #literalism #perception #philosophy #reading_religious_texts #religion #solipsism #subjectivism #the_bible #the_quran #theology

A moral absolute is a statement that is implied to be utterly correct and divine in nature. Some say that our understanding of divine law is a requirement for our being judged worthy enough to enter heaven - especially if our actions are supposed to live up to the standard. Therefore, it becomes essential that moral guidelines are readable from the believer's holy book in an absolute and inerrant way. Such thinking is a cornerstone of fundamentalism. But where a holy text can appear to very definitely uphold one person's opinions there are always others who are sure that it does not. Christianity, Islam and other religions with sacred texts have splintered bitterly into many factions as a result of differing interpretations of the same text. It seems there is something wrong with the idea that texts can be read objectively.

Despite what some religious folk claim, especially Christians and Muslims, it simply isn't possible to have a "Book of Truth" that can be read objectively, with a shared meaning agreed upon by everyone, especially when it comes to moral instruction and ethics. It is impossible to derive "absolute morals" from holy books like The Bible and The Qur'an. Unfortunately, because many religionists think that correct interpretation is of extreme importance, then, all these different possible conclusions lead to schism and the formation of competing denominations, often violently opposed to others who haven't come to the same conclusions.

Language: When we read, our brains interpret the words according to our understanding of language. Prof. Loughlin warns about this when it comes to lawmaking. He says "language has an open-textured quality", "there is an inherent vagueness in the ordinary use of language [...] and, because of this, rules - even if we accept that they have a core of settled meaning - are often surrounded by a penumbra of uncertainty [... and] often acquire meaning within particular contexts"42. Thomas Paine gave us the same warning, saying that "Human language is local and changeable, and is therefore incapable of being used as the means of unchangeable and universal information"43.

Subjectivism: Our own wild experiences in life, our own flawed understandings, both conspire continually to colour everything we see in the world. In epistemology, this basic fact is called subjectivism and the subjective nature of our perception of reality is one of the oldest topics in human philosophy, going back thousands of years44.

“Subjectivism is a problem of epistemology (theory of knowledge). The word describes the fact that we can only understand the world through our own senses and our own rational deliberations, in conjunction with our own limited experience in life. Our brains are imperfect organic machines, not a mystical repository of truth. Our senses are imperfect, our point of view limited, and the reality we experience is never the total picture. Our divergent contexts result in each of us interpreting, understanding and perceiving the world differently to one another even when looking at the same stimulus. Human thought is infused with systematic thinking errors. Our knowledge of absolute reality is hampered by our limited insights and imperfect brains, and we can never truly escape from the shackles of our own minds. Our total take on reality is a mix of guesses and patchwork. These problems have been debated by the most ancient philosophers, thousands of years ago, and no practical answers have yet been forthcoming.44.”

"Subjectivism and Phenomenology: Is Objective Truth Obtainable?"

Vexen Crabtree (2017)Personal Bias: When people approach a religious text or any large book from which they intend to derive ethical teachings, nearly without exception the person will pick up the book and pay very particular attention to all the morals they already agree with. The philosopher George Smith says that "Christian theologians have a strong tendency to read their own moral convictions into the ethics of Jesus. Jesus is made to say what theologians think he should have said"45. A homophobe will pick up the Christian Bible and realise that homosexuality is an evil sin. A misogynist will pick up the Bible or Qur'an and realise that after all this time he's right: Women are inferior, and he can quote the Bible or Qur'an to prove it. A fluffy liberal will read it and find all the hippy love-thy-neighbour bits and therefore will be able to prove that all those homophobes and misogynists have it wrong. In arguing against extremism, Neil J. Kressel46 points out that "everyone picks and chooses, at least a little. Everyone interprets"47.

Complexity and Contradictions: Long texts that dance with moral issues suffer from the problem that some morals in one place step on the toes of other morals in other parts. The debates over which verses have precedence over others is a major symptom of this issue. In addition because of the volume of text and its frequent obscurity and complexity, there is plenty of scope for the imagination, and for personal bias, to find a way to interpret lines in a way that beat to the drum of the reader. Because of the kaleidoscope of different plotlines and levels of possible interpretation, one's subconscious and imagination is given accidental freedom to invent all kinds of morals.

Most Holy Books' Texts is Not About Morals: Most stories in holy books are about personalities - tales about what people are said to have done what. Most of them also involve war and cultural struggles between different peoples, and are often written from within one particular geographical area. It is possible to read these stories and take out of them a wide range of morals, and therefore, to think that these indirect lessons have divine mandate. The same occurs with all long texts. Take Tolkien's Lord of the Rings - it is very much like the Bible (in style), and it is clear to see that you could spend your entire life analyzing it for morals. Many people who undertook such a task would come to different conclusions, just as with Holy Books. The simple fact remains that the parts of the text that say "Here follows a moral rule, to be obeyed by all people for all time" are very infrequent indeed. The Qur'an is much more frank than the Bible, but is still mostly about the retelling of events.

See if you can work out if the following questions are being raised with regards to The Lord of the Rings, The Bible, or the Qur'an:

The people in the book all have their own aims, which are relevant to the topic of the book and the life circumstances of that person. Most people's actions are simply not centered around any wish to provide universal instruction on behaviour - it's all about their problems at that time.

Using characters from within this book we would find many seemingly contradictory morals. For example, for the side of Good, there is much killing to be done, yet part of the morals is that the bad guys kill people.

People interpret the "real meanings" behind various stories in hugely varying ways, and volumes of books have been written on such interpretations based on political and moral undertones.

The answer is that this describes all large books written by Humans. Attempts to read them as places for moral instruction is itself the problem, and the cause of schism, violent disagreements and fundamentalism.

Cultural Context: As time passes, the original cultural assumptions and cultural understanding of phrases and words will all change, making it impossible for many things to be understood by future audiences in the same way that the original authors meant them. The longer ago something was written, the less the context is clear to us today, and this opens the way for much culturally subjective opinion. "Love thy neighbour as thyself" has meant various things at various times: A land of barbarians may feel quite free to brutalize others just as they brutalize themselves48, whereas band of 1970s hippies spread love in a much more physical way. Over time, morals are simply read into texts differently, hence why religious prohibitions change over time too. We read text literally, chronologically and philosophically, but both The Koran and much of The Bible was written in prose, in poetry, using many symbolic aspects and word games. Shifts in time and place mean that there are unknown cultural references that we cannot possibly understand now, even if text that we think we are reading correctly.

Translations: All of the above problems come together when translations of holy texts are made. One thing that fundamentalists do get right is their determined and enviable attempts to read scripture in its original language (which is easier for Muslim Arabs who still speak the same language the Koran was written in). But we have very few of the original texts of our major religions. We rely on copies-of-copies-of-copies, which at some point, have often been translated - quotations changed from Aramaic to Greek, entire texts from Latin to English, based on Greek translations. We know that even from very early on numerous mistranslations have been introduced49, such as the mistaken usage of the word "virgin" to describe the prophecy of Jesus' birth since the major Septuagint translation.

It is surprising that anyone thinks a god would attempt to communicate with us in any particular language, let alone ancient ones. If I was god, I would transmit my message directly into everyone's brain. That way problems with translation and subjectivism would be removed and people could make informed decisions and moral choices based on the full facts, rather than miscommunicated ideals. This would end all translation and transmission problems too.

Clearly, no gods have imparted such a universal moral message into the minds of mankind. If there is a supreme and omniscient creator god then it is responsible for creating the way that our brains work. Such a being knows that we can only interpret life subjectively, and that no text will mean the same thing for any two people. Therefore by design, any sacred text must only be designed by God for the specific culture into which the text arose.

3.2. Determining Which Holy Book Contains Divine Morals50

This section is taken from Fundamentalism and Literalism in World Religions.

Fundamentalists largely hold that their scripture is the only authority we have as regards to the truth: It is an absolute truth. However, in order to select which text they consider inerrant there must first be non-scriptural basis for this selection. Before a person considers a text inerrant, they are in a position where their position in the world dictate their knowledge of religious texts and their approach to them. These secular and coincidental factors determine whether a person comes to decide that a text is inerrant.

“Koran, n. A book which the Mohammedans foolishly believe to have been written by divine inspiration, but which Christians know to be a wicked imposture, contradictory to the Holy Scriptures.”

"The Devil's Dictionary" by Ambrose Bierce (1967)51

The philosopher Immanuel Kant made the same argument in 1785 with regards to believers choosing that the God of the Bible is indeed a being of moral perfection: "Even the Holy One of the Gospels must first be compared with our ideal of moral perfection before we can recognise Him as such"52. It is an illogical situation that once a fundamentalist has chosen a text, they then deny that they have no other source of authority: If there is no source of authority other than the text they've chosen, then their reason for selecting the text has become invalid. Beyond this point of self-contradiction it can be seen that the reasons are complex psychological ones.

Fundamentalists have been unable to arrive at a logical criterion for how a secular living person should select which text is true out of all the religious texts available in the world, all of which have adherents who claim their chosen books are inerrant.

Through Prophecy? All claim that correct prophecies validate their text, and all claim that all the other texts don't really have correct prophecies. It is impossible to investigate all such claims yourself, in one lifetime, so it appears that a logical intellectual choice based on prophecy is impossible. Or it is ignorant: A choice can't be made without ignorance until a person has actively investigated all claims of prophecy by all religious texts. Until the individual has done this, they're merely guessing which one can be judged, by criteria of its prophecies, to be "more" divine than other texts.

Sensible possibility: That God has inspired multiple correct prophecies in multiple religious texts or that magic operates as part of the natural laws of the universe, and supernatural prophecy-making is possible whether or not God has a part in it. Of all the prophecies that have not come true (such as the thousands made about the end of the world, etc), you could very sensibly infer that any true prophecies are only true by coincidence and luck, not by supernatural means. In all cases, it can be seen that judging religious texts by their prophecies is a poor method.

Through Faith? Decisions by "faith" are determined in 99% of cases by cultural and societal factors, by psychology, and not by virtue of which text is true. Faith is a cultural and psychological phenomenon. Or, of course there is the chance that a God does actually support multiple (even contradictory) religions, and therefore that it doesn't really matter which one you pick.

Through Morals? It is circular logic to claim that a text is an absolute authority on morals, and then to claim that you can judge a text by the morals contained in it, before knowing which text is true. If you assume particular morals, then look at religious texts, you will end up selecting the text that most matches your own morals. If you select a text then claim that its morals are absolutely correct, you could have drawn exactly the same conclusion no matter which religious text you'd selected. The factors which determine which one you select in the first place are therefore purely cultural and psychological - not moral. We have no rational basis for claims of what morals God considers best. Selection by morals is a fundamentally flawed selection criteria, requiring either genuine stupidity, ignorance or doublethink.

By Popularity? If you judged by popularity you would conclude that at the moment the Christian text is 'absolute' and correct. But, in previous centuries, Roman paganism was absolute and correct, and before that, the animist worship of multiple simple spirits was the correct set of beliefs. It makes no sense that to say that now, at the moment, a particular religion is true merely because it is popular. Especially given that within a religion such as Christianity, there are many varied beliefs. To base claims on popularity is to undermine the idea that one particular religion has correct beliefs.

For more on the topic of how religionists approach their chosen texts, see:

- Criteria of Selection

- Arguing Against Literalism: It Is Impossible to Read Text Objectively

- Liberals Take Scripture More Seriously

4. Human Rights and Secular Morals: Ethics Without Religion or Faith

#atheism #ethics #human_rights #morals #religion #religious_morals #secular_morals #theism

If the secular Human Rights approach is correct, if it engenders good morals and civility and progress, then, there should be statistical evidence which can be consulted to support or detract from it. There is, indeed, such evidence.

Source:12

The Social and Moral Development Index concentrates on moral issues and human rights, violence, public health, equality, tolerance, freedom and effectiveness in climate change mitigation and environmentalism, and on some technological issues. A country scores higher for achieving well in those areas, and for sustaining that achievement in the long term. Those countries towards the top of this index can truly said to be setting good examples and leading humankind onwards into a bright, humane, and free future. See: Which are the Best Countries in the World? The Social and Moral Development Index. The graph here shows clearly that social and moral development is at its highest in countries that are the least religious. As religiosity increases, each country suffers from more and more conflicts with human rights, more problems with tolerance of minorities and religious freedom, and problems with gender equality.

For more, see:

Further reading: